Lunar eclipse of aught-eight

Warning: I wrote this blog in 2008. That is a long time ago, especially on the internet. My opinions may have changed since then. Technological progress may have made this information completely obsolete. Proceed with caution.

While looking for information on yesterday’s lunar eclipse, I found NASA’s solar eclipse website which has maps of every solar eclipse from 2000 BC to 3000 AD in 20-year blocks. I took a look through these, it seems like I only get three chances to see a solar eclipse in my lifetime, assuming: 1) I live in this general area of the planet my whole life; 2) I don’t want to travel more than 5-6 hours to see one; and 3) I live to be at least 96 years old.

The first opportunity has already passed by: a partial solar eclipse on May 30, 1984 which passed right over my hometown. I don’t remember it; I guess I was too two to care.1

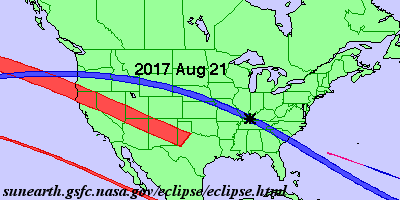

However, on Monday, August 21, 2017, a total solar eclipse will pass by very close to where I currently live. I’m thinking on that day I’ll take the day off work and head out to somewhere in the western North Carolina mountains to see the eclipse. If anyone wants to join me then go ahead and mark your calendar.

The third opportunity for me to see an eclipse will be May 11, 2078. I will be 96.5 years old then, so I’m not sure if I’ll still care (assuming, of course, that I’m still alive, which is statistically improbable).

One last thing that I couldn’t think of a way to segue into: there is an interesting story about how Christopher Columbus used a lunar eclipse to save his life. Sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

-

I seem to recall an eclipse happening when I was in middle school. I know it didn’t get dark or anything, but I think it got a little bit dimmer outside. This must have been the May 10, 1994 partial solar eclipse, although the path of the eclipse was several hundred miles from North Carolina.